Thank you all for your comments/thoughts/reflections on my Vinyl Revival post - it's an issue that seems to go 'round and 'round in circles, like a record; it seems no linear argument can be made in relation to illegal downloads and the demise of the Music Industry.

In this first post, I'll address the issues and Qs raised by Anonymous who writes:

"Thank you for the article. However, some very broad claims are made without providing argument or empirical support. For example:

"It is universally acknowledged that the free-(down)loaders are not those who would normally pay for their music to begin with". What is the evidence for this assessment?"

It is the pervading belief (some would say Music Industry meme) that college students are the ones most responsible for the illegal downloads, and the segment that has been targeted and pursued by the Recording Industry Association of America.

Music piracy crackdown nets college kids: "They're targeting the worst people," UNL freshman Andrew Johnson, who also settled for $3,000. "Legally, it probably makes sense, because we don't have the money to fight." Johnson got his e-mail in February, with the recording industry group's first wave of letters targeting college students. He had downloaded 100 songs on a program called LimeWire using the university network. The money to settle came from the 18-year-old's college fund. He'll work three jobs this summer to pay back the money."

The best and most cogent research on the subject that I've found on the subject was authored by Harvard Business Professor Felix Oberholzer-Gee and co-authored by Koleman Strumpf: "The Effect of File Sharing on Record Sales"

(discussed here). Sean Silverthorne writes a great piece entitled "Music Downloads: Pirates—or Customers?" and interviews Felix Oberholzer-Gee, summarizes Gee's research. She writes:

"The researchers believe that most downloading is done over peer-to-peer networks by teens and college kids, groups that are "money-poor but time-rich," meaning they wouldn't have bought the songs they downloaded."

Critical of Gee's research, Barry Neil Shrum writes:

"Oberholzer-Gee and Stumpf erroneously concluded that the impact of illegal file-sharing on the music industry was, in their words, "null" but have since revised their conclusions and now argue that illegal file sharing is responsible for about 20% of the decline in the decline of revenue in the music industry."

While 20% is still significant, it accounts for far less of the overall decline than the RIAA would have us believe. I think a comparison can be made to those (of us) who (used to) tape their music from the radio in our high school and college days. This was an act of passion as well as prudence.

It has always been my belief, based on my experience and reading, that those who download music illegally are overall the most fervid ((some would say rabid)) music listeners, who start off as 'freeloaders' and grow up to be just-as-avid legal consumers.

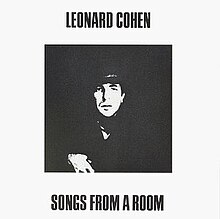

It has always been my belief, based on my experience and reading, that those who download music illegally are overall the most fervid ((some would say rabid)) music listeners, who start off as 'freeloaders' and grow up to be just-as-avid legal consumers.The first album I ever saved-up for and bought was Leonard Cohen's 'Songs from a Room', and album I still lovingly remove from its sleeve, rub clean and play on my turntable. For the most part, I taped my music off the radio and bought records on the rare occasion of my absolute-inner-need-to-have-it. And while I'm not excusing or condoning illegal downloads, I do think that the focus on this segment of music listeners has created a myopic and lopsided conversation on the topic of the current state of the Music Industry.

This 'inner-need' to have (that is 'own') the music one loves is felt across all generations, and I would argue that this need is only felt when music reaches true depth. There's a new generation of listeners who are still saving up their money to buy the music they must have on vinyl: 'The Police', 'Pink Flloyd', 'Led Zepplin', as well as 'Radiohead', Tom Krell, and Vampire Weekend.

The second point Anonymous makes: "Also, how does one explain the precipitous decline in music sales once downloading (and CD copying) became an option? If it were possible to completely stop piracy, I suspect there would be sudden increase in legal music purchasing."

In answering this point, the numbers continue to confound everyone:

Digital Music Leads Boost in Record Sales: "What’s the biggest surprise in the music industry this year? Music sales are actually up for the first time since 2004."

I would argue that this increase has less to do with file-sharing sites being shuttered than it has to to with other factors that are seldom if ever considered or measured:

* listeners are becoming more enamored by the music they are acquiring

* music is becoming more portable and intrinsic to people's lives

* the price-point for singles has dropped to .99

There is also an ongoing debate as to why CD sales have declined - Some attribute this to a decline in overall album output by major record labels:

When Is Downloading Music on the Internet Illegal?: "Organizations that support music sharing and downloading however have thrown a wrench into the statistics released by the music industry as they suggest some of these losses are due to a bad economy and fewer "new releases" hitting the market in some of those years. It is obvious that the music industry has to be losing some money due to Internet music file sharing, but finding the exact amount lost due to music downloading isn't so simple."Others attribute this to a 'disenchanted' listening public:

A $13 billion fantasy: latest music piracy study overstates effect of P2P: "The IPI study also assesses the increased demand for music if piracy didn't exist and assumes the market would remain as "intensely competitive" as it is today. The problem is that music fans are largely disenchanted with the market. By and large, music fans think that music is too expensive and that much of what is available isn't very good. 58 percent of those responding to a study commissioned by Rolling Stone magazine and the Associated Press said that music is declining in quality. And although the DRM situation is looking up these days, it can still be a confusing morass with unanticipated side effects for consumers..."

While yet others question the statistics to begin with:

RIAA's Statistics Don't Add Up to Piracy - "The RIAA's damage is all self-inflicted.They blamed the demise of the CD single on piracy, but the truth is that they just stopped making them, at least in the U.S. In 2003, they apparently decided they didn't need to make albums any longer and went back to selling singles. An industry with a 90% failure rate cuts its new product offering by more than 80% over a four year period. Then it starts suing people because sales are down and it's obviously all the fault of the single mothers, college kids and dead people."

I think a multi-dimensional view of the Music Industry is necessary, (see 'Chaos Theory' and 'Phase Space'): instead of thinking in one dimensional terms, perhaps a more compex analysis is needed - one that measures not only purchasing habits over time, but emotional and visceral dynamics through time and space - that is:

* purchasing trends as they correspond to how emotionally attached listeners are to the music they are compelled to buy

* the overall income of those who purchase CDs vs downloads

* how LEGAL downloads (offered daily by RCRD LBL, for example) have affected buying habits

* whether SoundScan (the industry standard) factors in small, lesser known and distributed record labels, when measuring CD sales

Julie Samuels in her excellent article "It’s Time for the Recording Industry to Stop Blaming "Piracy" and Start Finding A New Way" writes:

* purchasing trends as they correspond to how emotionally attached listeners are to the music they are compelled to buy

* the overall income of those who purchase CDs vs downloads

* how LEGAL downloads (offered daily by RCRD LBL, for example) have affected buying habits

* whether SoundScan (the industry standard) factors in small, lesser known and distributed record labels, when measuring CD sales

Julie Samuels in her excellent article "It’s Time for the Recording Industry to Stop Blaming "Piracy" and Start Finding A New Way" writes:

"As many — EFF included — have been saying for years, filesharing is not the reason that the recording industry has fallen on hard financial times. In fact, the recording industry's complaints that the sky is falling really only apply to the recording industry, and not musicians and the fans, who have seen increased music purchases, increased artist salaries, and the availability of more music than ever before. And now two new reports further debunk the recording industry's myth.

First, the London School of Economics released a paper finding that while filesharing may explain some of the decline in sales of physical copies of recorded music, the decline "should be explained by a combination of factors such as changing patterns in music consumption, decreasing disposable household incomes for leisure products and increasing sales of digital content through online platforms." And even if the sales of recorded music are down, there is an important distinction to draw: the recording industry may be hurting, but the music industry is thriving. For example, the LSE paper points out that in the UK in 2009, the revenues from live music shows outperformed recorded music sales."

There's a tendency - indeed, a need - to see the world in black and white, to understand it in logical terms, as though every issue and dilemma has a straight trajectory that we can graph and plot. But like weather patterns, species extinction, the secret life of ants, and the sound of caterpillars, there are some things that will forever reside in the realm of the unknown, beyond, perhaps, our full understanding... and, like a spinning LP, we can only circle around that mystery...

No comments:

Post a Comment